Mulan (1998 film)

| Mulan | |

|---|---|

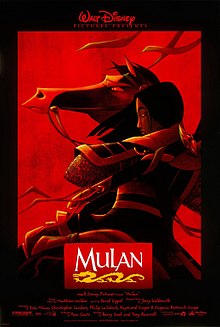

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Robert D. San Souci |

| Based on | Ballad of Mulan by Guo Maoqian |

| Produced by | Pam Coats |

| Starring | |

| Edited by | Michael Kelly |

| Music by | Jerry Goldsmith |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Pictures Distribution[a] |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 87 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $90 million[1] |

| Box office | $304.3 million[2] |

Mulan is a 1998 American animated musical coming-of-age[3] action-adventure film produced by Walt Disney Feature Animation for Walt Disney Pictures. Based on the Chinese legend of Hua Mulan, the film was directed by Barry Cook and Tony Bancroft and produced by Pam Coats, from a screenplay by Rita Hsiao, Chris Sanders, Philip LaZebnik, and the writing team of Raymond Singer and Eugenia Bostwick-Singer, and a story by Robert D. San Souci. Ming-Na Wen, Eddie Murphy, Miguel Ferrer, and BD Wong star in the English version as Mulan, Mushu, Shan Yu, and Captain Li Shang, respectively, while Jackie Chan provided the voice of Li Shang for the Chinese dubs of the film. The film's plot takes place in China during an unspecified Imperial dynasty, where Fa Mulan, daughter of aged warrior Fa Zhou, impersonates a man to take her father's place during a general conscription to counter a Hun invasion.

Mulan was the first of three features produced primarily at the Disney animation studio at Disney-MGM Studios (now Disney's Hollywood Studios) in Bay Lake, Florida. Development for the film began in 1994, when a number of artistic supervisors were sent to China to receive artistic and cultural inspiration.

Mulan premiered at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles on June 5, 1998, and was released in the United States on June 19. The film was well received by critics and the public, who praised the animation, plot, characters (particularly the title character), and musical score. It grossed over $304 million worldwide against a production budget of $90 million. It earned a Golden Globe and Academy Award nomination and won several Annie Awards, including Best Animated Feature. It was then followed by a direct-to-video sequel, Mulan II in 2004. A live-action remake directed by Niki Caro was released on September 4, 2020.[4]

Plot

The Huns, led by the ruthless Shan Yu, invade Han China by breaching the Great Wall. The Emperor orders a general mobilization, with conscription notices requiring one man from each family to join the Imperial Army. Fa Mulan, an adventurous young woman, hopes to bring honor to her family. She is arranged to meet a matchmaker to demonstrate her fitness as a future wife, but is deemed a disgrace after several mishaps.

Fa Zhou, Mulan's elderly father and a renowned military veteran, is conscripted. Mulan tries dissuading him from going, but he insists that he must do his duty. Fearing for his life, she cuts her hair and takes her father's sword and armor, disguising herself as a man so that she can enlist in his stead. Quickly learning of her departure, Mulan's grandmother prays to the family's ancestors for Mulan's safety. In the family's temple, the spirits of the ancestors are awakened by Mushu, a small red dragon who is a disgraced former family guardian. The Great Ancestor decides that the powerful stone dragon guardian should guide Mulan, and sends Mushu to wake him. After accidentally destroying the guardian's statue, Mushu decides to redeem himself to the ancestors by personally aiding Mulan.

Reporting to the training camp, Mulan passes as a man named "Fa Ping", with Mushu providing encouragement and clumsy guidance throughout her deception. Under the command of Captain Li Shang, she and her fellow recruits—including three named Yao, Ling, and Chien-Po—gradually become trained soldiers. The Emperor's belligerent counsel, Chi-Fu, threatens to dissuade the Emperor from allowing Shang's men to fight. Mushu then writes a fake letter from Shang's father, General Li, ordering Shang to follow the main imperial army into the mountains. The reinforcements set out and discover that the Huns have slaughtered Li and his troops.

As the soldiers march up a mountain pass, the Huns ambush them. Mulan uses a Huolongchushui cannon to trigger an avalanche and bury the Huns, but is badly injured. Shang and the soldiers discover Mulan's true gender while her wound is bandaged. Instead of executing Mulan as the law requires, Shang spares her life and expels her from the army before departing for the Imperial City to report the Huns' defeat. Mulan, however, later discovers Shan Yu and several of his warriors have survived.

Mulan travels to the city to warn Shang just as the Huns seize the palace and take the Emperor hostage. In the ensuing fight, Shan Yu's men are quickly defeated and Mulan lures Shan Yu onto the roof, and ultimately pins him down with his own sword. Guided by Mulan, Mushu uses a skyrocket to propel Shan Yu into a fireworks launching tower, killing him. The Emperor and the city's assembled inhabitants praise her for having saved them, and they bow to her in honor. She accepts the Emperor's crest and Shan Yu's sword as gifts but declines his offer to join the royal council. Mulan returns home and presents these gifts to her father, but he ignores them, happy to have her back. Having become enamored with Mulan, Shang also arrives and accepts her invitation to stay for dinner. Mushu is reinstated as a Fa family guardian as the ancestors celebrate.

Cast

- Ming-Na Wen as Mulan (singing voice provided by Lea Salonga)

- Eddie Murphy as Mushu

- BD Wong as Captain Li Shang (singing voice provided by Donny Osmond)

- Harvey Fierstein as Yao

- Gedde Watanabe as Ling (singing voice provided by Matthew Wilder)

- Jerry Tondo as Chien-Po

- James Hong as Chi-Fu

- Miguel Ferrer as Shan Yu, the Hun chieftain

- Soon-tek Oh as Fa Zhou

- Freda Foh Shen as Fa Li

- June Foray as Grandmother Fa (singing voice provided by Marni Nixon)

- Frank Welker as Khan (Mulan's horse), Cri-Kee (Mulan's cricket), and Hun

- Miriam Margolyes as The Matchmaker

- James Shigeta as General Li

- George Takei as First Ancestor

- Pat Morita as The Emperor of China

- Mary Kay Bergman as various ancestors[5]

Kelly Chen, Coco Lee and Xu Qing voiced Mulan in the Cantonese, Taiwanese Mandarin and Mainland standard versions of the film respectively, while Jackie Chan provided the voice of Li Shang in all three Chinese versions and appeared in the version of promotional music videos of "I'll Make a Man Out of You". Taiwanese comedian Jacky Wu provided the voice of Mushu in the Mandarin version.

Production

Development

In 1989, Walt Disney Feature Animation Florida had opened with 40 to 50 employees,[6] with its original purpose to produce cartoon shorts and featurettes.[7] However, by late 1993, following several animation duties on Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, and The Lion King, Disney executives were convinced to allow the Feature Animation Florida studios to produce their first independent film.[8] Around that same time, Disney Feature Animation developed an interest in Asian-themed legends, beginning with the optioning of several books by children's book author Robert D. San Souci, who had a consulting relationship with Disney executive Jay Dyer.[9] Also around that time, a short straight-to-video film titled China Doll about an oppressed and miserable Chinese girl who is whisked away by a British Prince Charming to happiness in the West was in development. Thomas Schumacher asked San Souci if he had any additional stories, in response to which San Souci turned in a manuscript of a book based on the Chinese poem "The Song of Fa Mu Lan". Ultimately, Disney decided to combine the two separate projects.[10][11]

Following the opening of the Feature Animation Florida studios, Barry Cook, who had served as a special-effects animator since 1982,[12] had directed the Roger Rabbit cartoon Trail Mix-Up produced at the satellite studio. At a lunch invitation with Thomas Schumacher, Cook was offered two projects in development: a Scottish folk tale with a dragon or Mulan. Knowledgeable about the existence of dragons in Chinese mythology, Cook suggested adding a dragon to Mulan, in which a week later, Schumacher urged Cook to drop the Scottish project and accept Mulan as his next project.[13] Following this, Cook was immediately assigned as the initial director of the project,[14] and cited influences from Charlie Chaplin and David Lean during production.[15] While working as an animator on the gargoyles for The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Tony Bancroft was offered to co-direct the film following a recommendation from Rob Minkoff, co-director of The Lion King, to Schumacher, in which he accepted.[16] He joined the creative team by early 1995.[17]

In 1994, the production team sent a select group of artistic supervisors to China for three weeks to take photographs and drawings of local landmarks for inspiration; and to soak up local culture.[18] Key members of the creative team at the time—Pam Coats, Barry Cook, Ric Sluiter, Robert Walker, and Mark Henn—were invited to travel to China as a research trip to study the landscape, people, and history of the original legend. From June 17 to July 2, 1994, the research trip flew to Beijing, China, which is where Coats became inspired by the placement of flags on the Great Wall. They also toured Datong, Luoyang, Xi'an, Jiayuguan, Dunhuang, and Guilin.[19]

Writing

In its earliest stages, the story was originally conceived as a Tootsie–inspired romantic comedy film where Mulan, who was a misfit tomboy who loves her father, is betrothed to Shang, whom she has not met. On her betrothal day, her father Fa Zhou carves her destiny on a stone tablet in the family temple, which she shatters in anger, running away to forge her own destiny.[20] In November 1993, Chris Sanders, who had just finished storyboard work on The Lion King, was hoping to work on The Hunchback of Notre Dame until Schumacher appointed him to work on Mulan instead.[21] Acting as Head of Story, Sanders grew frustrated with the romantic comedy aspect of the story, and urged producer Pam Coats to be more faithful to the original legend by having Mulan leave home because of the love for her father.[22] This convinced the filmmakers to decide to change Mulan's character in order to make her more appealing and selfless.[23]

Sequence Six—in which Mulan takes her father's conscription order, cuts her long hair, and dons her father's armor—served as a pivotal moment in the evolution of Mulan's character. Director Barry Cook explained that the sequence initially started as a song storyboarded by Barry Johnson and redrawn by character designer Chen-Yi Chang. Following the story changes to have Mulan leave to save her father, the song was dropped. Storyboard artist and co-head of story Dean DeBlois was tasked to revise the sequence, and decided to board the sequence with "minimal dialogue".[24] Assisted with an existing musical selection from another film score courtesy of Sanders, the sequence reel was screened for Peter Schneider and Thomas Schumacher, both of whom were impressed. DeBlois stated, "Sequence Six was the first sequence that got put into production, and it helped to establish our 'silent' approach."[25] Additionally, General Li was not originally going to be related to Shang at all, but by changing the story, the filmmakers were able to mirror the stories of both Shang's and Mulan's love for their fathers.[26] As a Christian, Bancroft declined to explore Buddhism within the film.[27][better source needed]

Because there was no dragon in the original legend, Mulan did not have animal companions; it was Roy E. Disney who suggested the character of Mushu.[15] Veteran story artist Joe Grant created the cricket character, Cri-Kee, though animator Barry Temple admitted "the directors didn't want him in the movie, the story department didn't want him in the movie. The only people who truly wanted him in the movie were Michael Eisner and Joe Grant – and myself, because I was assigned the character. I would sit in meetings and they'd say, 'Well, where's the cricket during all this?' Somebody else would say, 'Oh, to hell with the cricket.' They felt Cri-Kee was a character who wasn't necessary to tell the story, which is true."[28] Throughout development on the film, Grant would slip sketches of Cri-Kee under the directors' door.[29]

Casting

Before production began, the production team sought out Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, or Korean vocal talents.[30] Tia Carrere was an early candidate to voice the title character.[31] However, Lea Salonga, who had been the singing voice of Princess Jasmine in Aladdin, was initially cast to provide both Mulan's speaking and singing voices, but the directors did not find her attempt at a deeper speaking voice when Mulan impersonated Ping convincing, so Ming-Na Wen was brought in to speak the role. Salonga returned to provide the singing voice.[32] Wen herself landed the role after the filmmakers listened to her narration at the beginning of The Joy Luck Club. Coats reflected on her decision, stating, "When we heard Ming-Na doing that voice-over, we knew we had our Mulan. She has a very likable and lovely voice, and those are the qualities we were looking for."[33]

For the role of Mushu, Disney was aiming for top Hollywood talent in the vein of Robin Williams' performance as the Genie in Aladdin.[33] The filmmakers initially approached Joe Pesci and Richard Dreyfuss until Michael Eisner considered Eddie Murphy.[34] After accepting the role, Murphy initially balked when he was asked to record at the Disney studios, but then asked to record the voice in his basement at his Bubble Hill mansion in Englewood, New Jersey.[35]

For the speaking voice of Captain Li Shang, BD Wong was hired,[36] although his singing voice, for the song "I'll Make a Man Out of You", was performed by Donny Osmond, who had previously auditioned to be the speaking voice of the title character in Hercules.[37] Osmond's casting originated from a suggestion from the casting director,[37] and throughout recording, Osmond studied Wong's dialogue tapes, and aimed to match his inflections and personality.[38] Osmond commented that his sons decided that he had finally "made it" in show business when he was in a Disney film.[39] Likewise for the role of Grandmother Fa, June Foray provided the speaking voice, and Marni Nixon supplied the singing voice.[40]

Mimi Chan was chosen by Mark Henn as the model and martial arts video reference for Mulan. Character drawing sessions and live-action video reference shooting was done over the course of three years.[41] Chan's cousin, George Kee, was chosen to play the part of Captain Shang Li. Together, they choreographed fight sequences for the film's song “I’ll Make a Man Out of You” and the film's end finale.[42]

Animation and design

To achieve a harmonious visual look, producer designer Hans Bacher and art director Ric Sluiter, along with Robert Walker and Head of Backgrounds Robert Stanton collaborated to establish a proper chronological location for the film in Chinese history. Since there was no general consensus on the time of Mulan's existence, they based the visual design on the Ming and Qing dynasties.[43] An important element of Bacher's design was to turn the art style closer to Chinese painting, with watercolor and simpler design, as opposed to the details of The Lion King and The Hunchback of Notre Dame.[44] Bacher further studied more than thirty-five film directors ranging from the silent era German Expressionism, British and American epics of the 1950s and 60s, and the Spaghetti Westerns for inspiration for composition, lighting, and staging that would establish settings that enhanced the characters.[45] Additional inspiration was found in the earlier Disney animated films such as Bambi, Pinocchio and Dumbo to establish a sense of staging.[46]

In October 1997, the Walt Disney Company announced a major expansion of its Florida animation operations constructing a 200,000-square-foot, four-story animation building and the addition of 400 animators to the workforce.[47]

To create 2,000 Hun soldiers during the Huns' attack sequence, the production team developed crowd simulation software called Attila. This software allows thousands of unique characters to move autonomously. A variant of the program called Dynasty was used in the final battle sequence to create a crowd of 3,000 in the Forbidden City. Pixar's photorealistic open API RenderMan was used to render the crowd. Another software developed for this movie was Faux Plane, which was used to add depth to flat two-dimensional painting. Although developed late in production progress, Faux Plane was used in five shots, including the dramatic sequence which features the Great Wall of China, and the final battle sequence when Mulan runs to the Forbidden City. During the scene in which the citizens of China are bowing to Mulan, the crowd is a panoramic film of real people bowing. It was edited into the animated foreground of the scene.[48]

Music

The songs featured in the film were written by composer Matthew Wilder and lyricist David Zippel. Stephen Schwartz was originally commissioned to write the songs for the film.[49] Following the research trip to China in June 1994, Schwartz was contacted by former Disney studio chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg to compose songs for The Prince of Egypt, which he agreed. Peter Schneider, then-president of Walt Disney Feature Animation, threatened to have Schwartz's name removed from any publicity materials for Pocahontas and The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Michael Eisner phoned Schwartz, and urged him to back out of his commitment to DreamWorks, but he refused and left the project.[50] After Schwartz's departure, his three songs, "Written in Stone", "Destiny", and "China Doll", were dropped amid story and character changes by 1995.[51][52] Shortly after, Disney music executive Chris Montan heard Matthew Wilder's demo for a stage musical adaptation of Anne Rice's Cry to Heaven, and selected Wilder to replace Schwartz.[51] In July 1997, David Zippel joined to write the lyrics.[53] The film featured five songs composed by Wilder and Zippel, with a sixth originally planned for Mushu, but dropped following Eddie Murphy's involvement with the character.[54]

Although Danny Elfman and Thomas Newman were considered to score the film, English composer Rachel Portman was selected as the film composer. However, Portman became pregnant during production, and decided to back out.[16] Following Portman's departure, Randy Edelman—whose Dragonheart theme was used in the trailer—and Kitarō were considered,[51] until Jerry Goldsmith became available and signed on after dropping out of a project.[16] The film's soundtrack is credited for starting the career of pop singer Christina Aguilera, whose first song to be released in the U.S. was her rendition of "Reflection", the first single from the Mulan soundtrack. The song, and Aguilera's vocals, were so well received that it landed her a recording contract with RCA Records.[55] In 1999, she would go on to release her self-titled debut album, on which "Reflection" was also included. The pop version of "Reflection" has a Polish version ("Lustro" performed by Edyta Górniak) and two Spanish versions, for Spain (performed by Malú) and Hispanic America (performed by Lucero). Other international versions include a Brazilian Portuguese version by Sandy & Junior ("Imagem"), a Korean version performed by Lena Park, and a Mandarin version by Coco Lee.

The music featured during the haircut scene, titled Mulan's Decision, is different in the soundtrack album. The soundtrack album uses an orchestrated score while the movie uses heavy synthesizer music. The synthesizer version is available on the limited edition CD.[56] Salonga, who often sings movie music in her concerts, has done a Disney medley which climaxes with an expanded version of "Reflection" (not the same as those in Aguilera's version). Salonga also provided the singing voice for Mulan in the film's sequel, Mulan II.

Release

Marketing

The film's teaser trailer was released in June 1997, attached to the theatrical releases of Hercules, The Little Mermaid and Flubber.[57] Teaser spots were shown during CBS's coverage of the 1998 Winter Olympics.[58]

Because of the disappointing box office performances of The Hunchback of Notre Dame and Hercules, Disney restricted its marketing campaign for Mulan, spending $30 million on promotional advertisements compared to more than $60 million for Hercules the year before.[59] Rather than holding a lavish media event premiere like those of the past few years, such as premiering Pocahontas in Central Park and bringing the Main Street Electrical Parade to Fifth Avenue for Hercules, Disney opted to premiere the film on June 5, 1998, at the Hollywood Bowl, complete with Chinese lanterns and fortune cookies.[59][60] Two days before the general release, McDonald's launched its promotional campaign by including one of eight toys free with the purchase of a Happy Meal.[61] The promotion also included Szechuan sauce for its Chicken McNuggets, which would be referenced in a 2017 episode of the Adult Swim series Rick and Morty and subsequently brought back by McDonald's as a promotional item related to that show.[62]

In collaboration with Disney, Hyperion Books published The Art of Mulan authored by Jeff Kurtti, which chronicled the production of the film. In addition with its publication, Hyperion Books also issued a collector's "folding, accordion book" of the ancient poem that inspired the film.[63] On August 18, 1998, around 3,700 backpacks and 1,800 pieces of luggage were recalled back to their manufacturer, Pyramid Accessories Inc., when it was discovered they contained lead-based paint.[64]

Home media

The film was first released on VHS on February 2, 1999, as part of the Walt Disney Masterpiece Collection lineup. Mulan was released on DVD on November 9, 1999, as a Walt Disney Limited Issue for a limited sixty-day time period before going into moratorium.[65] On February 1, 2000, it was re-released on VHS and DVD as part of the Walt Disney Gold Classic Collection lineup.[66] The VHS and DVD were accompanied by two music videos of "Reflection" and "True to Your Heart" while the DVD additionally contained the theatrical trailer and character artwork.[67] The Gold Collection release was returned into the Disney Vault on January 31, 2002.[68] On October 26, 2004, Walt Disney Home Entertainment re-released a restored print of Mulan on VHS and as a 2-disc Special Edition DVD.[69]

In March 2013, Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment released Mulan and Mulan II on Blu-ray and DVD to coincide with the film's 15th anniversary.[70]

In September 2017, Mulan became available to Netflix users through their streaming service.[71] In November 2019, Mulan became available for streaming on Disney+. A year later, Mulan was released on 4K Blu-ray.[72]

Reception

Box office

Mulan grossed $22.8 million in its opening weekend,[2] ranking second behind The X-Files.[73] It went on to gross $120 million in the United States and Canada combined, and $304 million worldwide, making it the second-highest grossing family film of the year, behind A Bug's Life, and the seventh-highest-grossing film of the year overall.[74] While Mulan domestically out-grossed the previous two Disney animated films which had preceded it, The Hunchback of Notre Dame and Hercules, its box office returns failed to match those of the Disney films from the first half of the Renaissance such as Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, and The Lion King.[75] Internationally, its highest grossing releases included those in the United Kingdom ($14.6 million) and France ($10.2 million).[76]

Critical reception

Upon release, Mulan received mostly positive reviews from film critics,[77][78][79] who praised it for exploring themes such as strength, feminism,[80] and gender roles.[81] The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes gave the film an approval rating of 92%, based on 142 reviews, with an average rating of 7.9/10. The site's consensus reads, "Exploring themes of family duty and honor, Mulan breaks new ground as a Disney film, while still bringing vibrant animation and sprightly characters to the screen."[82] In a 2009 countdown, Rotten Tomatoes ranked it seventeenth out of the fifty canonical animated Disney features.[83] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 72 out of 100, based on 24 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[84] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film a rare "A+" grade.[85]

Roger Ebert, reviewing for the Chicago Sun-Times, gave Mulan three-and-a-half stars out of four in his written review. He said that "Mulan is an impressive achievement, with a story and treatment ranking with Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King".[86] Likewise, James Berardinelli of ReelViews awarded the film three-and-a-half stars out of four praising the lead character, its theme of war, and the animation. He concluded that "Adults will appreciate the depth of characterization while kids will love Mulan's sidekick, a colorful dragon named Mushu. Everyone will be entertained [by] the fast-moving plot and rich animation."[87] Todd McCarthy of Variety called the film "a female empowerment story par excellence, as well as a G-rated picture that may have strong appeal for many adults." McCarthy further praised the voice cast and background design, but overall felt the film "goes about halfway toward setting new boundaries for Disney’s, and the industry's, animated features, but doesn't go far enough."[88] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly graded the film a B+ writing, "Vividly animated, with a bursting palette that evokes both the wintry grandeur and decorative splendor of ancient China, Mulan is artful and satisfying in a slightly remote way."[89]

Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune described the film as "a big disappointment when compared with the studio's other recent films about a female hero searching for independence." He was further critical of Mulan's characterization in comparison to Ariel and Belle, and claimed the "design of the film does not take advantage of the inspiration provided by classic Chinese artists, and the songs are not memorable."[90] Similarly, Janet Maslin of The New York Times criticized the lack of detail in the background art and described it as "the most inert and formulaic of recent Disney animated films."[91] Reviewing the film for the Los Angeles Times, Kenneth Turan wrote "Mulan has its accomplishments, but unlike the best of Disney's output, it comes off as more manufactured than magical." While he praised the title character, he highlighted that the "by-now-standard hip patter (prepare for jokes about cross-dressing) is so tepid that not even five credited writers can revive it, and the songs by Matthew Wilder and David Zippel (with Lea Salonga and Donny Osmond singing for the leads) lack the spark that Zippel's lyrics brought to the underappreciated Hercules."[92] Ed Gonzalez of Slant Magazine criticized the film as "soulless" in its portrayal of East Asian society.[93]

This movie was also the subject of comment from feminist critics. Mimi Nguyen says the film "pokes fun at the ultimately repressive gender roles that seek to make Mulan a domesticated creature".[94] Pam Coats, the producer of Mulan, said that the film aims to present a character who exhibits both masculine and feminine influences, being both physically and mentally strong.[95]

Accolades

- In 2008, the film was one of 50 nominees listed on the ballot for the American Film Institute's top 10 greatest American animated movies.[107]

Reception in China

Disney was keen to promote Mulan to the Chinese, hoping to replicate their success with the 1994 film The Lion King, which was one of the country's highest-grossing Western films at that time. Disney also hoped it might smooth over relations with the Chinese government which had soured after the release of Kundun, a Disney-funded biography of the Dalai Lama that the Chinese government considered politically provocative.[108] China had threatened to curtail business negotiations with Disney over that film and, as the government only accepted ten foreign films to be shown in China each year,[109] Mulan's chances of being accepted were low.[110] Finally, after a year's delay, the Chinese government did allow the film a limited Chinese release, but only after the Chinese New Year, so as to ensure that local films dominated the more lucrative holiday market.[111][112] Publications have reported that critical and audience reception in China was negative overall,[79][113] who accused Disney of westernizing the tale.[114] Box office income was low, due to both the unfavorable release date and rampant piracy.[115] Chinese people also complained about Mulan's depiction as too foreign-looking and the story as too different from the myths.[116][115]

Legacy

The World History Encyclopedia has credited the film with introducing the Mulan legend to a wider audience, in turn inspiring greater interest in Chinese history and literature.[77]

Video game

A Windows, Macintosh, and PlayStation point-and-click adventure interactive storybook based on the film, Disney's Animated Storybook: Mulan (titled Disney's Story Studio: Mulan on PlayStation), was released on December 15, 1999. The game was developed by Media Station for computers and Revolution Software (under the name "Kids Revolution") for PlayStation.[117][118] The game was met with generally positive reception and holds a 70.67% average rating at the review aggregator website GameRankings.[119]

Live-action adaptation

Walt Disney Pictures first expressed interest in a live-action adaptation of Mulan in the 2000s. Zhang Ziyi was to star in it and Chuck Russell was chosen as the director. The film was originally planned to start filming in October 2010, but was eventually canceled.[120]

In 2015, Disney again began developing a live-action remake.[121] Elizabeth Martin and Lauren Hynek's script treatment reportedly featured a white merchant who falls in love with Mulan, and is drawn into a central role in the country's conflict with the Huns.[122] According to a Vanity Fair source, the spec script was only a "jumping-off point" and all main characters will in fact be Chinese.[123] Dawn of the Planet of the Apes and Jurassic World screenwriters Rick Jaffa and Amanda Silver are to rewrite Hynek and Martin's screenplay with Chris Bender, J. C. Spink and Jason Reed producing.[124] In February 2017, it was announced that Niki Caro will direct the live-action adaptation of the 1998 animated film.[125]

The casting process of a Chinese actress to portray the heroine began in October 2016. The film was originally scheduled to be released on November 2, 2018, but it was later taken off the release schedule with The Nutcracker and the Four Realms taking its old slot.[126][127] On November 29, 2017, Liu Yifei was cast as the titular character.[128] The film had its Hollywood premiere on March 9, 2020.[129] Disney originally scheduled the film to be released in theaters on March 27, 2020; however, this was pushed back to July 24, and then August 21.[130][131] The film's theatrical release was canceled in the United States and would instead have its premiere for a premium fee on Disney+ on September 4, 2020. It will still be released theatrically in countries where theaters have re-opened, such as China, as well as in other countries that do not have Disney+.[132]

Donnie Yen was cast as Commander Tung, a mentor and teacher to Mulan.[133] Following him, Jet Li joined the film as the emperor of China, Gong Li was cast as the villain, a witch, and Xana Tang was announced to play Mulan's sister.[134] The next month, Utkarsh Ambudkar was cast as Skatch, a con artist, and Ron Yuan was cast as Sergeant Qiang, the second in command of the Imperial Regiment.[135] In June, Yoson An was cast as Chen Honghui, "a confident and ambitious recruit" who becomes Mulan's love interest.[136] In July, Jason Scott Lee joined the cast as Bori Khan, a secondary villain and warrior seeking revenge.[137] In August 2018, Tzi Ma, Rosalind Chao, Cheng Pei-Pei, Nelson Lee, Jimmy Wong and Doua Moua were added to the cast.[138][139]

References in Disney media

Although Mulan isn't royalty by either birth or marriage (her husband is merely a high-ranking military officer), she is part of the Disney Princess media franchise. Mulan was the last addition to the lineup until Princess Tiana from The Princess and the Frog was added in 2009, 11 years later.[140] In the film Lilo & Stitch, Nani has a poster of Mulan in her room.[141] Mulan is also present in the Disney and Square Enix video game series Kingdom Hearts. In the first Kingdom Hearts and in Kingdom Hearts: Chain of Memories, Mushu is a summonable character,[142] and in Kingdom Hearts II, the movie is featured as a playable world named "The Land of Dragons", with the cast of the film reprising their roles (excluding Shan-Yu, now voiced by Corey Burton); in the first chapter, the film's plot is changed to accommodate the game's characters (Sora, Donald and Goofy) and Mulan (both as herself and as "Ping") able to join the player's party as a skilled sword fighter, while the second chapter covers Organization XIII member Xigbar as a spy in black and Mulan's determination to stop him with Sora's help.[142] Actress Jamie Chung plays a live-action version of Mulan in the second, third, and fifth seasons of the ABC television series Once Upon a Time.[143] The video game Disney Magic Kingdoms includes some characters of the film and some attractions based on locations of the film as content to unlock for a limited time.[144][145][146]

See also

- Han dynasty (the historical period on which this film is loosely based)

- Han–Xiongnu War (the historical conflict on which this film is loosely based)

- List of Disney animated features

- List of Disney animated films based on fairy tales

- List of animated feature-length films

- List of traditional animated feature films

Notes

- ^ Distributed by Buena Vista Pictures Distribution through the Walt Disney Pictures banner.

- ^ Tied with Antz, A Bug's Life, and The Prince of Egypt

References

- ^ "Mulan". The-Numbers. Nash Information Services. Archived from the original on June 27, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ a b "Mulan (1998)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Lyons, Jessica (February 4, 2023). "'Turning Red' & 9 Other Great Disney Coming-of-Age Movies". Collider. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (August 4, 2020). "'Mulan' Going On Disney+ & Theaters in September; CEO Bob Chepak Says Decision Is A "One-Off", Not New Windows Model". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ "Ancestors". Archived from the original on March 25, 2011. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ Pack, Todd (January 13, 2004). "Disney Animation Unit Fades Away in Orlando". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on December 13, 2014. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Hinman, Catherine (November 19, 1990). "Disney Dips into Local Inkwell Florida Animation Team Lends Hand To 'Rescuers' 'rescuers'". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on November 19, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ King, Jonathon (December 26, 1993). "New Home, Same Magic". Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- ^ Kurtti 1998, p. 27.

- ^ Brown, Corie; Shapiro, Laura (June 8, 1998). "Women Warrior". Newsweek. Archived from the original on July 13, 2021.

- ^ Whipp, Glenn (June 19, 1998). "'Mulan' Breaks the Mold with Girl Power; Newest Heroine Isn't Typical Disney Damsel Waiting for Her Prince to come". Los Angeles Daily News. TheFreeLibrary.com. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ Hinman, Catherine (July 15, 1992). "How The Disney Film Short 'Off His Rockers' Made It to the Big Screen: A Little Project That 'blew Up.'". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Kurtti 1998, p. 30.

- ^ Abbott, Jim (June 21, 1998). "Florida Animation Studio Comes of Age with Mulan". Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- ^ a b Vincent, Mal (June 20, 1998). "With "Mulan," Disney bids for another classic". The Virginian-Pilot. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ a b c Tony Bancroft (August 14, 2008). "Tony Bancroft balances the yin and the yang in directing Mulan" (Interview). Interviewed by Jérémie Noyer. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ Kurtti 1998, p. 38.

- ^ "Discovering Mulan" (Documentary film). Mulan DVD: Walt Disney Home Entertainment. 2004.

- ^ Kurtti 1998, pp. 46–67.

- ^ Kurtti 1998, pp. 108–11.

- ^ Kurtti 1998, p. 34.

- ^ Kurtti 1998, p. 111.

- ^ "Finding Mulan" (Documentary film). Mulan DVD: Walt Disney Home Entertainment. 2004.

- ^ Kurtti 1998, pp. 173–75.

- ^ Kurtti 1998, p. 176.

- ^ Hicken, Jackie (June 24, 2014). "50 things you might not know about your favorite Disney films, 1998–2013 edition". Deseret News. Archived from the original on August 25, 2018. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ Martin, Sami K. (March 12, 2013). "Tony Bancroft on 'Mulan': 'I Want to Bring Christian-Based Values to All My Work'". The Christian Post. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- ^ Kurtti 1998, p. 147.

- ^ "13 Things You Didn't Know About Mulan". Disney Blog. March 21, 2015. Archived from the original on June 5, 2015. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ Schaefer, Stephen (June 16, 1998). "Disney's newest heroine fights her own battles in 'Mulan'". The Boston Herald. Archived from the original on February 20, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Tsai, Michael (June 21, 2002). "'Lilo' captures Hawai'i spirit in an appealing way". The Honolulu Advertiser. Archived from the original on October 14, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Hischak, Thomas S. (2011). Disney Voice Actors: A Biographical Dictionary. McFarland. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-7864-6271-1. Archived from the original on September 24, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- ^ a b Vice, Jeff (June 19, 1998). "'Mulan' ala Disney". The Deseret News. Archived from the original on July 1, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Belz, Aaron (March 11, 2013). "The Maker of Mulan's Mushu Speaks". Curator Magazine (Interview). Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ Pearlman, Cindy (June 14, 1998). "'Mulan' earns her stripes // Disney banks on a brave new girl". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Vancheri, Barbara (June 17, 1998). "Busy Donny Osmond makes a captain sing". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. pp. E1, E3. Archived from the original on July 13, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2015 – via Google News Archive.

- ^ a b Pearlman, Cindy (June 30, 1998). "'Donny & Marie': Round 2". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- ^ "Ex-teen idol Osmond provides voice of Shang". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. Knight Ridder. June 26, 1998. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Scheerer, Mark (July 8, 1998). "Donny Osmond rolls with the punches for 'Mulan' success". CNN. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 11, 2007.

- ^ King, Susan (June 25, 1998). "Fa, a Long Long Way to Come". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 16, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ McElroy, Joey (October 19, 2022). "Fantasmic!' Returning to Disney's Hollywood Studios Nov. 3". Disney Parks Blog. Archived from the original on October 19, 2022.

- ^ "The Business Journals". www.bizjournals.com. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ Kurtti 1998, p. 72.

- ^ "Art Design" (Documentary film). Mulan DVD: Walt Disney Home Entertainment. 2004.

- ^ Kurtti 1998, pp. 84–86.

- ^ Kurtti 1998, p. 78.

- ^ Shenot, Christine (March 8, 1997). "Disney Expanding at Mgm, Building Animation Empire". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on October 3, 2015. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ Mulan DVD Commentary (DVD). Walt Disney Home Entertainment. 2004.

- ^ Gray, Tim (March 17, 1994). "Disney puts on a glitzy 'Lion' show". Variety. Archived from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ^ de Giere, Carol (September 8, 2008). Defying Gravity: The Creative Career of Stephen Schwartz from Godspell to Wicked. Applause Books. pp. 250–252. ISBN 978-1-557-83745-5.

- ^ a b c "The Music of Mulan". OoCities. 1997. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ^ "Stephen Schwartz comments on Other Shows and Songs" (PDF). stephenschwartz.com. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 31, 2014. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ^ Variety Staff (July 24, 1997). "Disney's Spade Sting-along". Variety. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ^ "Songs of Mulan" (Documentary film). Mulan DVD: Walt Disney Home Entertainment. 2004.

- ^ Smith, Andy (August 15, 1998). "One talented teen". The Providence Journal. Big Noise. Archived from the original on September 19, 2010. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- ^ Clemmensen, Christian (July 7, 2007). "Filmtracks: Mulan (Jerry Goldsmith)". Filmtracks.com. Archived from the original on July 2, 2007. Retrieved July 28, 2007.

- ^ "In Hollywood, the earliest 'buzz' gets the gold". Los Angeles Daily News. The Albuquerque Tribune. November 11, 1997. p. D4. Archived from the original on December 15, 2022. Retrieved November 11, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "See MULAN During the Olympics!". The Twilight Bark. Burbank, California: Walt Disney Feature Animation. February 6, 1998. Retrieved November 11, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Eller, Claudia; Bates, James (June 12, 1998). "Bridled Optimism". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ "USA: WALT DISNEY PRESENTS ITS LATEST ANIMATED EXTRAVAGANZA "MULAN"". ITN. May 30, 1998. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ "McDonald's Launches First Global Kids' Meal Offer". Los Angeles Times. June 16, 1998. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Kuchera, Ben (October 9, 2017). "The Szechuan sauce fiasco proves Rick and Morty fans don't understand Rick and Morty". Polygon. Archived from the original on October 9, 2017. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- ^ "Disney banks on books". Variety. June 12, 1998. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ "Mulan backpacks, luggage recalled due to lead paint". The Daily News (Kentucky). Associated Press. August 18, 1998. Archived from the original on July 13, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2015 – via Google News Archive.

- ^ "Disney to Debut Nine Classic Animated Titles on DVD for a Limited Time to Celebrate the Millennium" (Press release). Burbank, California: TheFreeLibrary. Business Wire. August 17, 1999. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- ^ "Imagination for a Lifetime – Disney Titles All the Time; Walt Disney Home Video Debuts the Gold Classic Collection; An Animated Masterpiece Every Month in 2000" (Press release). Burbank, California: TheFreeLibrary. Business Wire. January 6, 2000. Archived from the original on May 22, 2018. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- ^ "Mulan – Disney Gold Collection". Disney. Archived from the original on August 15, 2000. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- ^ "Time is Running Out to Own Four of Disney's Greatest Classics!". Disney. December 2001. Archived from the original on November 14, 2018. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- ^ The Disney Animation Resource Channel (July 28, 2014). Mulan – 2-Disc Special Edition Trailer. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Review: Disney stays simple with "Mulan" I & II, "The Hunchback of Notre Dame" I & II, and "Brother Bear" 1 & 2 on Blu-ray". Inside the Magic. March 26, 2013. Archived from the original on September 10, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ Mallenbaum, Carly (August 23, 2017). "Netflix in September: Everything coming and going". USA Today. Archived from the original on October 9, 2017. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- ^ "Mulan Blu-Ray". Amazon. Archived from the original on July 13, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ "Box Office Report for X-Files". Box Office Reporter. Archived from the original on November 13, 2006. Retrieved August 11, 2007.

- ^ "1998 Worldwide Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (June 24, 2002). "Stitch in Time?". TIME Magazine. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Woods, Mark (December 7, 1998). "'Bug's' bags bucks". Variety. Archived from the original on March 17, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

- ^ a b Mark, Joshua J. (September 7, 2020). "Mulan: The Legend Through History". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

The film was generally well-received

- ^ Cooper, Gael (July 7, 2019). "First Mulan trailer for live-action remake blazes with grace, action". CNET. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

The original animated Mulan came out in 1998 and received positive reviews

- ^ a b Ouellette, Jennifer (September 5, 2020). "Review: Sumptuously reimagined Mulan turns Disney princess into a true warrior". Ars Technica. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- ^ Patidar, Ligna (September 21, 2020). "'Mulan (2020)': A beloved childhood story turned political controversy". The Miami Hurricane. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ Singh, Anvita (March 8, 2018). "The enduring feminism of Disney's Mulan". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on June 10, 2023. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ "Mulan". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on March 30, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ "Disney Animation Celebration". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on November 28, 2009. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- ^ "Mulan (1998) Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- ^ "Cinemascore". CinemaScore. 2012. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 19, 1998). "Mulan Movie Review & Film Summary (1998)". Roger Ebert. Archived from the original on August 25, 2018. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ^ Berardinelli, James. "Mulan (United States, 1998)". ReelViews. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (June 8, 1998). "Film Reviews: Mulan". Variety. Archived from the original on July 8, 2022. Retrieved December 14, 2022.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (June 19, 1998). "Mulan". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on August 25, 2018. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (June 19, 1998). "Mulder, Scully Make A Good Team". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on August 25, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (June 19, 1998). "FILM REVIEW; A Warrior, She Takes on Huns and Stereotypes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (June 19, 1998). "'Mulan': Formula With a New Flavor". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 30, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Gonzales, Ed (1998). "Review of Mulan". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Nguyen, Mimi. "Negotiating Asian American superpower in Disney's Mulan". Pop Politics. Archived from the original on February 18, 2008. Retrieved August 11, 2007.

- ^ Labi, Nadya (June 26, 1998). "Girl Power". TIME Magazine. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 11, 2007.

- ^ "The 71st Academy Awards (1999) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ^ "26th Annual Annie Awards". Annie Awards. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ "1999 Artios Awards". Casting Society of America. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ "1998 FFCC AWARD WINNERS". Florida Film Critics Circle. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "Mulan". Golden Globe Awards. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "41st Annual GRAMMY Awards". Grammy Awards. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ^ "1998 FMCJ Awards". International Film Music Critics Association. October 18, 2009. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ^ "3rd Annual Film Awards (1998)". Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ "International Press Academy website – 1999 3rd Annual SATELLITE Awards". International Press Academy. Archived from the original on February 1, 2008.

- ^ "International Press Academy website – 2005 9th Annual SATELLITE Awards". International Press Academy. Archived from the original on February 1, 2008.

- ^ "The 20th Annual Youth in Film Awards". Young Artist Awards. Archived from the original on November 28, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Chinese unimpressed with Disney's Mulan". BBC News. March 19, 1999. Archived from the original on January 12, 2014. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ "Foreign Films in China: How Does It Work?". China Film Insider. March 2, 2017. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ Michael Fleeman (1998). "Hollywood hopes more movies will follow Clinton to China". Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 5, 2011.

- ^ Kurtenbach, Elaine (February 8, 1999). "China Allows Disney Film Screening". Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- ^ Shelly Kraicer (August 14, 1999). "China vs. Hollywood : the BBC World Service talks to me". Archived from the original on June 21, 2007. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- ^ Smith-Wong, Katie (May 31, 2017). "Can a Mulan Live-Action Movie Work?". Den of Geek. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

The overall reception from Chinese audiences was negative

- ^ Yinmeng, Liu (September 6, 2020). "Mulan remake finally out-with Chinese characteristics". China Daily. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- ^ a b Langfitt, Frank (March 5, 1999). "Disney magic fails 'Mulan' in China". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on February 15, 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "Chinese unimpressed with Disney's Mulan". BBC News. March 19, 1999. Archived from the original on January 12, 2014. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- ^ "Disney's Story Studio: Mulan". GameSpot. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ "Disney's Story Studio: Mulan". Allgame. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ "Disney's Story Studio: Mulan". GameRankings. Archived from the original on August 25, 2012. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ "Zhang Ziyi to produce and star in 3D Mulan film" Archived February 27, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Channel News Asia. July 27, 2010. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- ^ Ford, Rebecca (March 30, 2015). "Disney Developing Live-Action 'Mulan' (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Fallon, Claire (October 10, 2016). "Original Live-Action 'Mulan' Script Reportedly Starred A White Love Interest". Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Desta, Yohana (October 10, 2016). "Don't Worry: Mulan Will Not Feature a White Male Lead". HWD. Archived from the original on August 14, 2020. Retrieved October 11, 2016.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (October 4, 2016). "Disney's Live-Action 'Mulan' to Hit Theaters in November 2018; Rick Jaffa and Amanda Silver Rewriting". Variety. Archived from the original on October 5, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Sun, Rebecca (February 14, 2017). "Disney's Live-Action 'Mulan' Finds Director (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (October 4, 2016). "Disney's Live-Action 'Mulan' Gets Winter 2018 Release Date". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 18, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Fuster, Jeremy (July 15, 2017). "Disney's 'Nutcracker and the Four Realms' Sets Fall 2018 Release, Bumping Live-Action 'Mulan'". The Wrap. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ^ Sun, Rebecca; Ford, Rebecca (November 29, 2017). "Disney's 'Mulan' Finds Its Star (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "'Mulan': First Reactions from the Premiere". The Hollywood Reporter. March 9, 2020. Archived from the original on March 21, 2020. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Erbland, Kate (June 26, 2020). "Disney Postpones 'Mulan' Theatrical Opening Again to August 21". Indiewire. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- ^ Whitten, Sarah (July 23, 2020). "Disney delays 'Mulan' indefinitely, Star Wars and Avatar movies pushed back a year". CNBC. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- ^ Low, Elaine (August 4, 2020). "'Mulan' to Premiere on Disney Plus as Streamer Surpasses 60.5 Million Subscribers". Variety. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ "Donnie Yen joins Mulan". Deadline. April 11, 2018. Archived from the original on April 12, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ^ Sun, Rebecca (April 12, 2018). "Disney's Live-Action 'Mulan' Lands Gong Li, Jet Li (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 13, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ N'Duka, Amanda (May 23, 2018). "'Mulan': Utkarsh Ambudkar & Ron Yuan Added To Disney's Live-Action Adaptation". Deadline. Archived from the original on July 11, 2019. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ Ford, Rebecca (June 6, 2018). "Disney Casts 'Mulan' Love Interest (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 6, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Sun, Rebecca (July 26, 2018). "Disney's 'Mulan' Adds Jason Scott Lee (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on July 26, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ ‘Mulan’ Rounds Out Cast As Filming Underway On Live-Action Movie Archived August 13, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Deadline Hollywood, Retrieved August 28, 2018

- ^ Disney’s ‘Mulan’ Casts Jimmy Wong & Doua Moua Archived August 14, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Deadline Hollywood, Retrieved August 28, 2018

- ^ "Disney Princess". Archived from the original on March 12, 2007. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ "Lilo & Stitch Easter Egg Archive". EEggs. Archived from the original on October 15, 2007. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ a b "Official Kingdom Hearts Website" (SWF). February 8, 2006. Archived from the original on June 18, 2007. Retrieved August 11, 2007.

- ^ Hibberd, James (July 6, 2012). "'Once Upon a Time' scoop: 'Hangover 2' actress cast as legendary warrior – EXCLUSIVE". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on July 6, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "Update 8: Mulan | Trailer". YouTube. January 26, 2017.

- ^ "Update 26: Mulan Part 2, Cinderella Part 3 | Livestream". YouTube. January 4, 2019.

- ^ "Update 56: Mulan | Livestream". YouTube. January 21, 2022.

Bibliography

- Kurtti, Jeff (1998). The Art of Mulan. Hyperion Books. ISBN 0-7868-6388-9.

External links

- 1998 films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s fantasy adventure films

- 1990s feminist films

- 1990s war films

- 1998 American animated films

- 1998 children's films

- 1998 musical films

- 1998 directorial debut films

- American animated feature films

- American animated musical films

- Animated films about discrimination

- Animated films about dragons

- Animated films about father–daughter relationships

- Animated films set in Imperial China

- Animated films set in palaces

- Animated musical films

- Animated war films

- Avalanches in film

- Best Animated Feature Annie Award winners

- Children's war films

- Cross-dressing in American films

- Disney Princess films

- Disney Renaissance

- Films about Hua Mulan

- Films about sexism

- Films directed by Barry Cook

- Films directed by Tony Bancroft

- Films scored by Jerry Goldsmith

- Films set in Beijing

- Films set in China

- Films set in the Han dynasty

- Films shot in Beijing

- Films shot in China

- Films with screenplays by Chris Sanders

- Films with screenplays by Philip LaZebnik

- Mulan (franchise)

- Walt Disney Animation Studios films

- English-language musical films

- English-language fantasy adventure films

- English-language war films

- Films with screenplays by Rita Hsiao

- Films produced by Pam Coats

- American feminist films